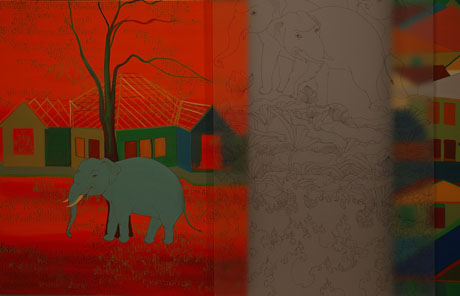

Two group of inter-panel polyptych work comprising panels of paintings with acrylic on canvas and drawing on transparent perspex (overall dimension of each work 250×500 cm) are part of my ongoing mural projects. The text The Journey of an Elephant accompany the work contains two languages. These works are part of the ongoing mural project since I left Thailand.

The works has involved material from my childhood background including the story Khiew Moo Pah which my late father wrote. My father recited the verse in Khiew Moo Pah routinely in front of the backdrop of his large mural. I was nine years and lived in the temple where he worked on the mural project. This part of my memories came back when I walked each morning in the Australian bush land during my Bundanon residency in 2003. The descriptive narration of the forest in E-Sarn, the North East of Thailand, his homeland in Khiew Moo Pah, later evolved into my work in response to the Australian bush land.

My works explores the visual imaginary of people in the interwoven into the society they migrated to and the interconnectedness via the imaginary of each migrant individual which sometimes never makes sense to others however related. I used iconographic elephants (Chang, the Thai word for elephant is the name I and my father shared) as imaginary figures in response to how I located the sense of my lived experience in my new home, and to express how an imaginary sense comes to occupy one’s own mind when relocated to a new place.

The Journey of the Elephant

Everyone may relate to the same stories and arguments, the same heroes and villains, but how do we relate to our co-nationals-the people we will not only never meet but those whom we will never see or hear? This is where the ‘imagined’ part of the community comes in. [i]

I am now going to tell you a story in Thai: you will not understand it, but you will understand why later.

ลอดกิ่งลอดก้าน คือก้าน คือกิ่ง ป่าย่อมเป็นป่า ทั้งรกทั้งสะอาด

ป่านาดอนหินแดงพิมูลโขงเจียม ป่าเพ็กสันเขา หนองบัวลุ่มภู ป่าไผ่ลาดไหล่เขา ลำธารบ้านมอญ

ต้นน้ำลำแควน้อยทองผาภูมิ แดนทอง ตอง ต้นตองกุง ตองชาด ลำน้ำสวย น้ำสวย สวยจนลายตาเหลือง ป่าดงรัก ดงรัก ดงจงอางพิษ เมืองขุขันฑ์ ป่าเหล่านั้นล้วนป่าดิบ ดิบ ป่าดงดิบ ดิบจนหนีไม่พ้นจากป่าฝ่าพงหลงป่า ชั่วชีวิต ชั่วระยะการเดินทาง ชั่วความคิดคนึง ของ คน

คน นี้แหละจึงต้องคนให้แหลก คนให้ทั่ว คนแต่ปลายเส้นผม จนถึงปลายเล็บตีน ถึงเรียกว่าคน

เมื่อไม่มีหนึ่งสองย่อมไม่มี

ป่าจึงคณานับเหลือลึกพันลึกกว้างใหญ่ไพศาล เท่าป่า

ป่าทั้งหลาย ร้อยป่าพันป่าเหล่านั้น

ตัดตอนจาก “เขี้ยวหมูป่า” โดย ไพบูลย์ สุวรรณกูฏ (๒๔๖๘-๒๕๒๕) คัดจากหนังสือ กันยายน นรินทร์ ของ สำนักพิมพ์ฟ้าเมืองไทย ๒๕๑๒ [ii]

The Thai excerpt is from a short story titled Khiew Moo Pa written by my father which was included in “Ganyayon Narintra” one of a series of well-known short-story series published during the 1970s in Thailand. My father often read this verse to his close friends, artists, poets and writers among contemporaries. He also read it occasionally to the followers and apprentices in his team of Thai temple mural painting. It was during that time in my childhood that I first heard the story. There were also times when my father sat and listened to me reading. I learned this version by heart and it has become a special musical tune staying within me. Indeed it has become my blood which contains everything that identifies me. But would it mean anything to my co-nationals in Thailand, let alone my other co-nationals in Australia? The prose contains various place-names of the already-vanished forests in the Thai jungle located mostly in E-Sarn, in north east of Thailand. They were places where my father had spent some time in his youth. Most of these names are quite unfamiliar even to Thai people. Nevertheless it may have been the answer of the life I have lived, and may have responded to most of what I have chosen to do. However I only recognised how significant it was for me, when I moved to and had spent some time in Australia. This secret tune is a kind of boundless entity that has connected me with the world in which I now live.

เมื่อไม่มีหนึ่ง สองย่อมไม่มี Where there is none, there is no two

The work, An Elephant Journey belongs to any individual who relates to this boundless entity. The Australian Bushland with its geographical identification, and the elephant with a very significant nature, both of which are like containers carrying something. Although they do not belong to each other, they look into one another and see the reflection of each other. What elephants see and what the landscape reveals, is the way I see myself attached to my new home. Chang (Thai word for elephant) was the nickname that my father gave me on the day I was born. It was also my father’s nickname, known from the way he mimicked the elephant walk. At fourteen he left his home in Ubon Rajathani, in order to find his own path. That was during the time when he stayed with his uncle who kept elephants for work in the E-sarn jungle of north-east Thailand. This part of his youthful experience is reflected in my father’s works; the plays, writings, poems and paintings. I am most comfortable when thinking about myself being an elephant. I carry my name as my totem. The tune in the Khiew Moo Pah may echo forever in me and the elephant may never depart. While it may remain personal, it is my utmost emotional contact with the world and how the world makes sense to me. An Elephant Journey observes how this secret tune plays its part with the place I am in. I use it as a language to communicate with other people, and how I would see myself attached to the other secret tunes, that are mingling in the shared space.

My father was a mural painter who set up his own group working in Thai Buddhist temple murals and hotel projects in Thailand during late 60s through early 80s. When he died in 1982, I took over the team and carried on the mural painting works for fourteen years until 1996 when I moved to Australia. It was during the years of painstaking training that I have acquired my skill. However, it was the part related to how I lived the world in my childhood, being the daughter of Paiboon Suwannakudt who raised his children in Buddhist temples along with his painting team, that has made me into who I am. An Elephant Journey reveals a visual interpretation of how I see myself in the world and it is dedicated to my father.

At Wat Theppon temple, I stayed in a wooden house provided for nuns. It was a remote temple situated among vegetable gardens and orchard in Talingchan, then in outer Bangkok. There was no road and everything was reachable only by small rowing-boats or on foot. My father and brothers normally slept in the main ordination hall where the mural painting took place. Girls were not allowed in overnight. My mother stayed at home with my elder sister to look after the house. Sometimes my other younger sister stayed in the temple with me, but at five years of age she was too young to be involved much. The nun’s house rarely had nuns around. It was isolated from the living quarters where all the monks stayed. This wooden house stood by a small canal and was surrounded with a row of little pagodas filled with bone and ashes from the deceased patrons of the temple. Next to the pagodas was an abandoned sandpit left over from the construction of the ordination hall. There were jackfruit trees between the sandpit and the ordination hall. This was my perfect play ground, where I played pretend cooking with the ingredients from trees. Sometimes I buried dead squirrels or birds I found killed by cats or dogs from the temple. I gave them chanting, the same way monks did during cremations. I would write down each name I gave for each burial the same way the pagodas contained persons’ names. During the day I could go in the ordination hall where I did cleaning for the team.

Sometimes I had to read to my father when he drew his sketches for the mural. They were Jataka stories about the life of Buddha and the other five hundred lives of the Bodhisattva reincarnations. The Bodhisattva monkey, the Bodhisattva deer, worm, bug, bee and all kinds of animals you could name. One day I found a whole group of many little snails just hatched from eggs. One by one I lined them up on a log and gave each name a Bodhisattva name from the Jataka. They looked like monks who sat up in line, chanting before and after each meal time. When I was eight I looked up at a tree and wondered what life after death would be like. The tree had butterfly shaped leaves with delicate white petals. I thought that in life after death, the tree would be a butterfly and I would very much like my reincarnation to be a female elephant.

The routine in Wat Theppon temple revolved around bell chimes. At four in the morning my routine chores started with sweeping the courtyard around the ordination hall. My two brothers were able to go with the monks to help carry food that they took as alms which were offered daily from the villagers nearby. As usual, being a girl I was not allowed to do the job. My father stayed behind sweeping the temple yard with me and that was how we began the day. He taught me the basic breath in and out meditation through this routine. It was years later before my father let me start practising by drawing individual leaves. I used the same meditation method while drawing hundreds of thousands of leaves and just that, day in day out, for years. During school days, when we were not at the temple, the day began at four with a morning walk through the village and orchard. We talked along the way and stopped occasionally to observe how different lives began their days at dawn. Going to school was another journey. The school we went to was newly opened in the area. In order to encourage enrolment, during the first years of the establishment the school daily offered the teachers to come and pick up children from home and school from different directions. With the distance our family were picked up first and dropped off last. We walked through vegetable gardens, markets, temples and orchards each day picking up other families en route and the same on the way back home each day. That was the most memorable part of my school year. However I lost my visual imagination and its stories to the school years where the world did not practically move the same way it was in the temple. Somehow within days after arriving Sydney, I found myself strolling along the lane and started giving name to trees around the suburb where I lived. I counted the trees that looked familiar to me and gave them a Thai name each. I collected about seventy names or so which matched the trees. The tune in Khiew Moo Pah resonated as ever.

What space is depends on who is experiencing it and how. [iii]

In my childhood I also saw that everyone in Thailand knew The Beatles and Elvis Presley. Every child in our neighbourhood could sing the title song from Japanese T.V. movie Ultra Hero. Our family did not own the first T.V. until I was fifteen but I could sing these songs long before that. The government of the day’s motto was งานคือเงิน เงินคืองาน บันดาลสุข “Work is money, money is work, our Happiness. There were placards and posters everywhere even in the local public health units or at schools which illustrated communism in the forms of demons, skeletons and other mean spirits. Having lived in the world where one lived from alms offered from others and having had to watch every breath you take while working, I felt myself totally a stranger in my own country. It reminded me of the Thai posters when I first came to Australia and was told that the singing of Christmas carols was being threatened or that the country was being swamped by others. Somehow the tune in Khiew Moo Pah had played its part in my settling in the new home.

I have connected myself to my new home in this country through trees. Three years after I arrived in Sydney I had one daughter and was then pregnant with another child. We moved into a bigger house. An old Korean couple decided to sell the house after living there for thirty years raising three sons. I went in at the back and saw the garden filled with vegetable and jars of kimchi and I felt like I was at home. I watched that same garden turning into a Thai garden with lemongrass, kaffir-lime, basil, galangals and chilli within weeks. Looking through the window where mango and banana leaves were dancing in the wind in my back garden, I was tempted to think that I had never been away from Thailand. It was when a Malaysian friend asked me for a mango branch to hang in front of her house to bring luck that I thought no more of being an insider or outsider. For the first time I could feel intimate with my co-nationals. We can relate with other people only through how we associate with the world that itself associates with others.

ลอดกิ่งลอดก้าน คืดก้านคือกิ่ง

ป่าย่อมเป็นป่า ทั้งรกทั้งสะอาด

The Thai phrase from Khiew Moo Pah plays its tune over and over in me. When the world is smaller with the fast forward technology of transportation and communication, people are more alienated and have more than ever become strangers to one another. I did not feel settled at first when I moved to Australia. It was the climate, food, language and so on and so forth you could blame. Above all it was the frustration of my studio practice that I felt like a fish taken out of water. Who would care for Thai mural painting anyway? The routine in which I observed the trees and gave them Thai names soothed my homesickness that I was able to express with the language that I am most comfortable with. This language is not Thai, is not even my skill in Buddhist temple painting, and is not the secret tune in me I inherited from my father, but it is the seeing the world with all that made me who I am. I use it to explore the world. The reward was, no matter how personal and how secret, that as I walked and looked up at the trees, all of a sudden people in the streets were not strangers to me anymore.

[i] Crang, M., Cultural Geography. New York, Routledge. 1998. p.164.

[ii] Panjapan, A., Ed. Ganyayon Narintra. Bangkok, Fah-Mueng-Thai, Bangkok Publishing. 1969. p.24.

[iii] Tilley, C. Y. A phenomenology of landscape : places, paths, and monuments. Oxford, UK & Providence, Rhode Island, Berg. 1994.